Different attempts at classification

Back to main indexThe classification of the living world has changed over time. The different versions are of course a reflection of the techniques available for studying organisms at the time. The first classification established by Aristotle as early as the 4th century BC was based on the naked eye observation of organisms. It persisted until the end of the 19th century and served as the philosophical basis for the Linnaean classification. It still continues to be implicitly used in common language. Classically, living beings were arranged in two groups: the animal kingdom and the plant kingdom. Animals were defined as living organisms endowed with reactions. That is to say that when they were touched, they showed a reaction, of retraction for example. Plants were defined as living beings capable of growth but devoid of reaction, as opposed to animals. This classification obviously did not take into account the microbes that had not yet been discovered! A third kingdom, the mineral kingdom, contained everything that did not grow, but on the contrary was eroding.

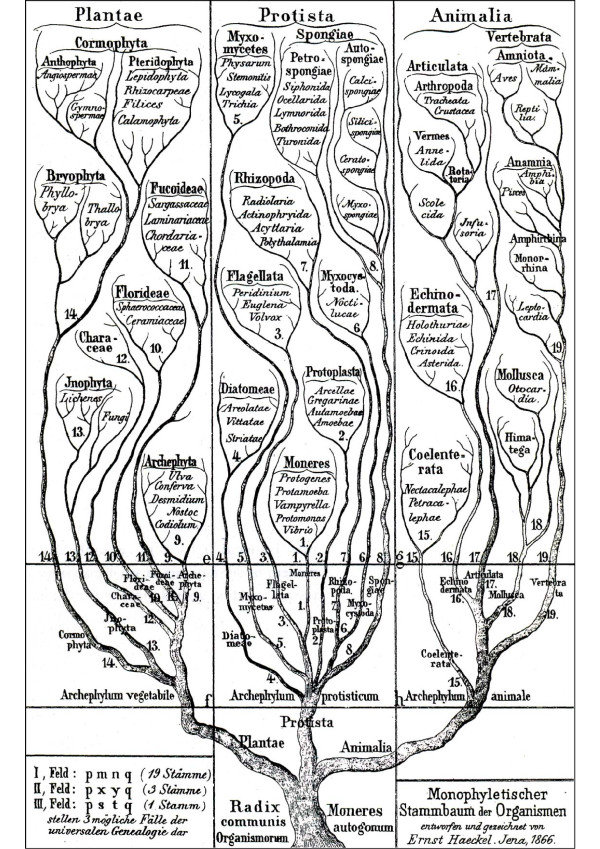

These definitions quickly became problematic because on the one hand groups of “plants” had animal characteristics, such as certain carnivorous plants or certain tropical mimosas which retract when touched, and on the other hand “animals” seemed devoid of reaction, especially the sponges which have long posed (and continue to pose!) problems for systematists. In the tree inFigure 63, for example, they are classified with protists. In the meantime, the microbes had been discovered, and some had rather animal-like characteristics, the protozoa, and others more plant-like, the “protophytes” and the fungi. However, many of them had characteristics that were neither really animal nor really plant: where are the motile algae, possessing flagella, placed? Where to classify myxomycetes which at one stage of their cycle behave like animals and at another like fungi? Their old name of mycetozoa, meaning “animal fungi”, reflects these questions.

Figure 63.

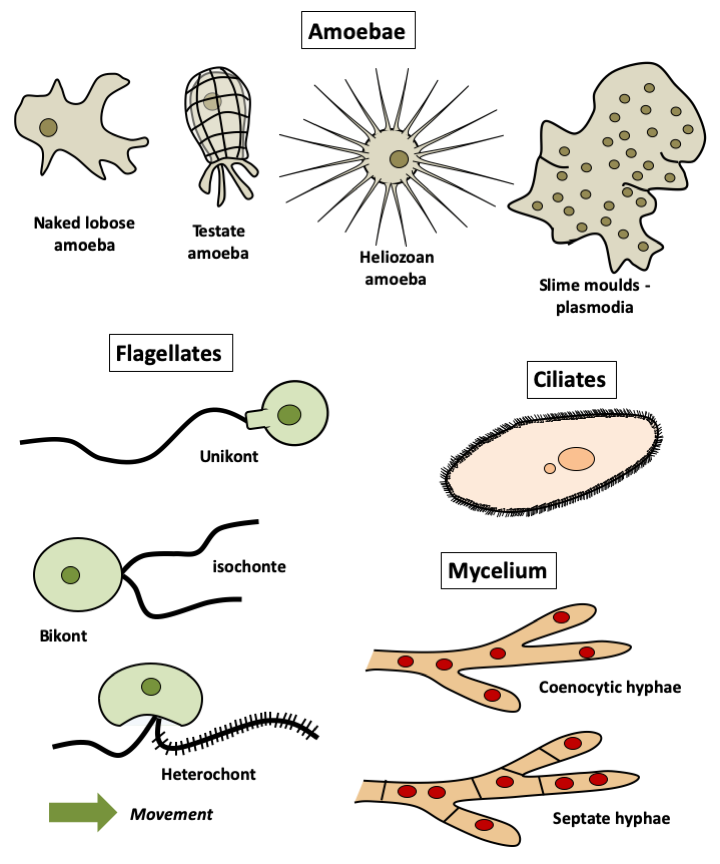

Ernst Haeckel's classification into 3 reigns (Generelle Morphologie der Organismen, 1866). In this classification fungi are considered as plants and sponges as protists.Gradually, during the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, more in-depth analyzes led to more complete and correct classifications, but without completely abandoning the animal/plant dichotomy. With regard to protists and fungi, the classification criteria were mainly based on the shape and motility of the organisms (Figure 64) and the trophic strategies, i.e. the feeding modalities of the organisms (Figure 65). For example, fungi were unquestionably plants, although unable to photosynthesize, and their study was the responsibility of botanists. The phagotrophic protists, because of their predatory behavior, belonged rather to the animal kingdom and were studied by zoologists. However, from 1860, Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) proposed a classification consisting of 3 kingdoms: animals, plants and protists (Figure 63). It kept the fungi and algae with the plants and the sponges with the protists.

Figure 64.

The forms adopted by eukaryotic cells have long been used as classification criteria.The discovery of fundamental differences in cell structure, made possible by the appearance of increasingly efficient optical and electron microscopes, offered new clues. In particular, absence of a nucleus in some cells and presence in others put an end to the animal/plant dichotomy. A new classification based on the eukaryotic/prokaryotic difference was however not immediately obvious. In fact, in the 1960s a classification based on “5 kingdoms” was proposed by Robert Whittaker (1920-1980). Prokaryotes were grouped together in the kingdom Monera, having the same rank as the other four: animals, plants, fungi and the catch-all group of protists. This classification was of very short duration, because with the advent of genetic and biochemical methods including DNA sequencing, it was quickly shown that bacteria had many fundamental differences not only at the level of their cellular structure, but also of their operation. In addition, these methods made it possible to identify as early as the mid-1970s an unknown group of living beings: the archaea. Currently, eukaryotes therefore form only one of the three kingdoms of life: Eukaryota, Bacteria and Archea. Since then, advances in molecular methods have made it possible to refine the classification of eukaryotes. This work is not complete, however, as new groups of protists remain to be discovered and the relationships between large group are still not fully clarified.

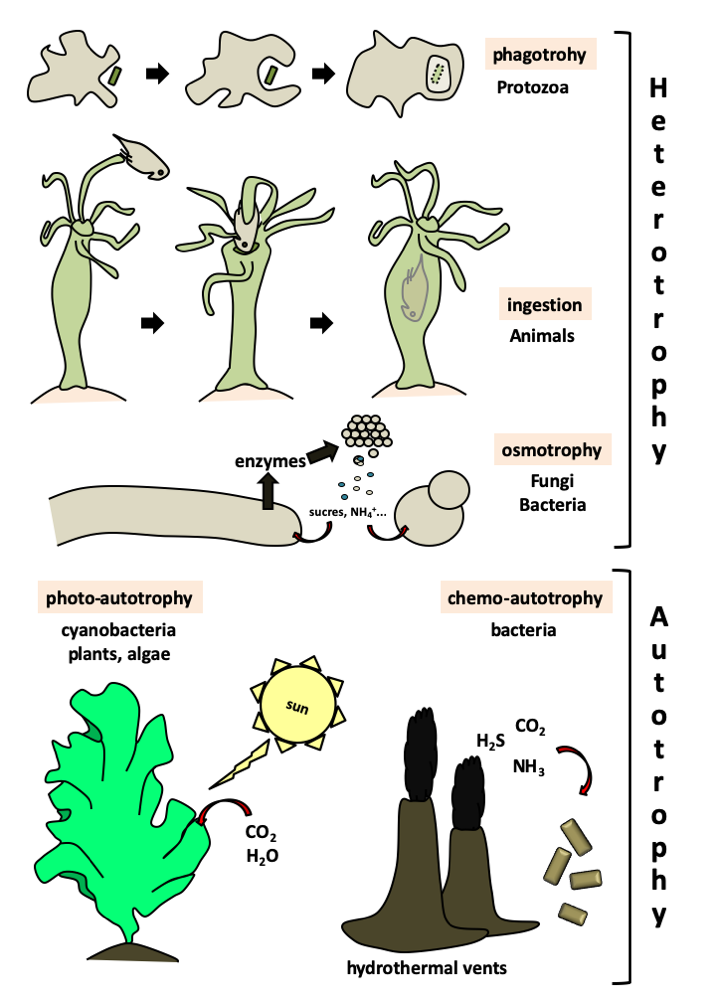

Figure 65.

Main trophic strategies of organisms. Trophic strategies have been used to define large groups of organisms. Protozoa are typically phagotrophs and animals feed by ingestion. Fungi and many parasites are osmotrophic (= absorbotrophic), that is, they digest food outside the cell when necessary; these are then absorbed via specific carriers. These organisms are heterotrophic, that is, they need already formed organic matter to live. On the contrary, autotrophs use minerals and a source of energy to make their own organic matter. If the source is light, they are said to be photo-autotrophic and they perform photosynthesis. In eukaryotes, algae and plants use this strategy. If they use chemical energy, like hydrogen sulfide, they are called chemo-autotrophs. Only bacteria are capable of chemo-autotrophy. Nevertheless, many eukaryotes live in symbiosis with such bacteria. Organisms which use two strategies simultaneously (often phagotrophy and photosynthesis) are said to be mixotrophic.Back to chapter index