Convergent and regressive evolution

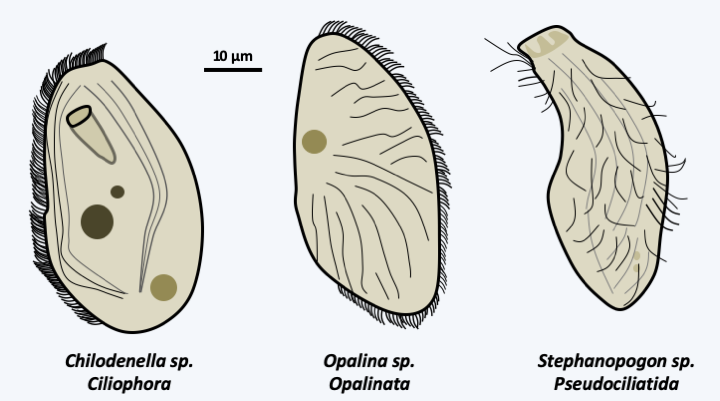

Back to main indexWe have seen that the classification of eukaryotic microorganisms has long relied on the analysis of life cycles, including morphological characters visible to the naked eye, with an optical or electron microscope, and trophic modes. Unfortunately for taxonomists, species have repeatedly adopted similar forms and lifestyles. This so-called convergent evolution results from the fact that when organisms are subjected to similar selection pressures, evolution often selects the same type of response: the most suitable! This results in morphological and/or biological resemblance that is often created by different means. For example, acquiring cilia appears to be a more efficient mode of locomotion than that performed with one or two flagella. This type of locomotion has been co-opted by at least three groups of protozoa, the Ciliophora, the Opalinata and the Pseudociliatida (Figure 73).

Figure 73.

Three unicellular ciliated protists with independent phylogenetic origins. These 3 protists have similar sizes and morphologies acquired by convergent evolution. From left to right: Chilodenella sp. from the Ciliphora group, Opalina sp. which is a Stramenopile, and Stephanopogon sp. which belongs to the group Discoba. Molecular clocks indicate that their ancestors diverged over a billion years ago.These events of converging evolution are very numerous and are found at all levels of phylogeny. The ancestors of the ciliates in Figure 73 probably diverged over a billion years ago. The Russula and Amanita carpophores (agaricomycetes; (Figure 74)) which are morphologically very close have also evolved by convergence, but much more recently. Indeed, Russulales and Agaricales probably diverged in the Jurassic (between 200 and 150 Ma ago). Their ancestors differentiated from skin-shaped carpophores. The acquisition of a foot promotes dispersion in the air by allowing the spores to originate from high places. That of a hat helps protect the spores from the rain.

Figure 74.

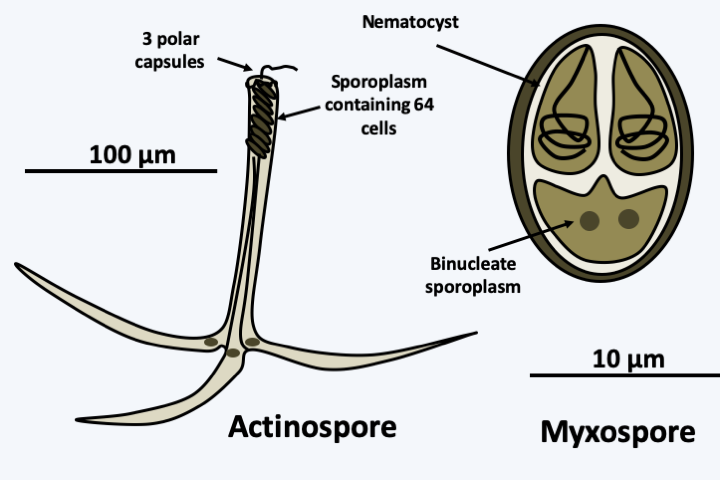

Russules (Russulales) Carpophores on the left and Amanites (Agaricales) on the right. The shape of these fruiting bodies has been acquired by convergent evolution.Regressive evolution, that is to say the simplification of organisms, which accompanies parasitism also often masks the kinship relations between organisms. The most illustrative example is probably that of the Myxozoa. These organisms are parasites alternating between a vertebrate and an aquatic invertebrate. While some species have retained a vermiform or pseudoplasmodial multicellular structure, most have a plasmodium or even amoeboid cells as trophic form. Their dispersion is via spores with a low number of cells and different morphologies depending on the host they leave (Figure 75). The phylogenetic position of these organisms has long been a mystery. Sequence analyses have shown that they are animals related to cnidarians, a position previously proposed on the basis of the presence in the spores of nematocysts and polar capsules, which are cells resembling cnidocysts of cnidarians.

Figure 75.

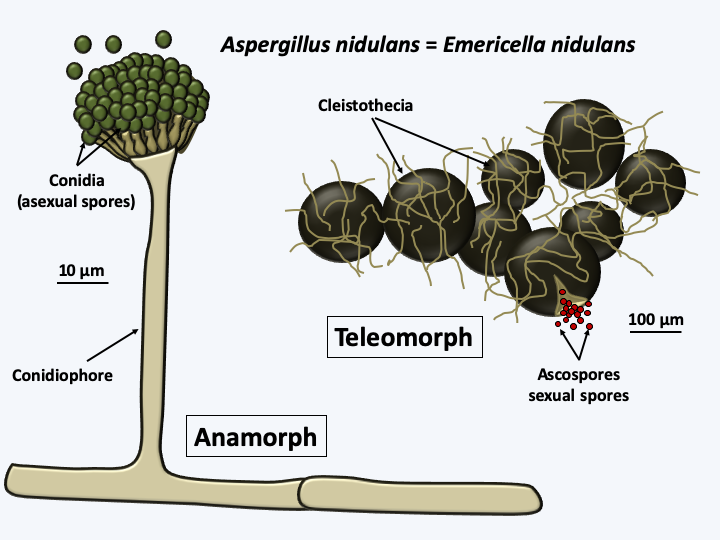

Spores of Myxobolus cerebralis, a myxozoan. Myxobolus cerebralis infects oligochaete annelids via myxospores and salmon via actinospores. Nematocysts and polar capsules allow adhesion and therefore facilitate penetration into the host of the sporoplasm. Once entered, these parasites develop in the form of amoeboid cells which will redifferentiate into spores at the end of the cycle.Unlike the convergent and regressive evolution which previously unified disparate organisms into polyphyletic groups, the differentiation sometimes put the same species in different groups. This is particularly striking in fungi, where the classifications on the so-called anamorphic and teleomorphic forms called for independent classifications. These forms are in fact different life stages of the same organism: the anamorph is the asexual sporophyte while the teleomorph is the sexual one. The forms may differ vastly in morphology, causing taxonomists to classify them as different organisms. The molecular data now allow the two classifications to be superimposed (Figure 76). Likewise, fungi can come in unicellular “yeast” or mycelial “mold” form. The form adopted depends either on environmental conditions or on the stage of development. For example, Mucor rouxii grows exclusively in the mycelial form when the atmosphere contains only N2. CO2 promotes development as yeast, while O2 inhibits it.

Figure 76.

Anamorph and teleomorph of the fungus Aspergillus/Emericella nidulans. The anamorphs and teleomorphs of this fungus have long been classified into two different classes: 'Deuteromycetes' for the anamorph and 'Plectomycetes' for the teleomorph. Obtaining both forms in culture from either a conidium or an ascospore has shown that they are two forms of the same species. Condiophores appear in cultures before cleistothecia. Molecular phylogenies have made it possible to classify it in the class of 'Eurotiomycetes', which includes the majority of ancient Plectomycetes. Normally, the official name of this fungus should be Emericella nidulans. But since it is better known as Aspergillus nidulans, it has kept this name.Back to chapter index