Eukaryotes without organelles?

Back to main indexWe have seen that the essential characteristic that distinguishes prokaryotes and eukaryotes is the presence of the nucleus and of the reticulum/golgi network associated with it. So far, there does not appear to be any organisms which one might assume to function like a typical eukaryote but for which the “nuclear” genomic DNA is not surrounded by a membrane or which does not possess the exo-/endocytosis system. However, there are some important exceptions to the structure and operation of the nucleus:

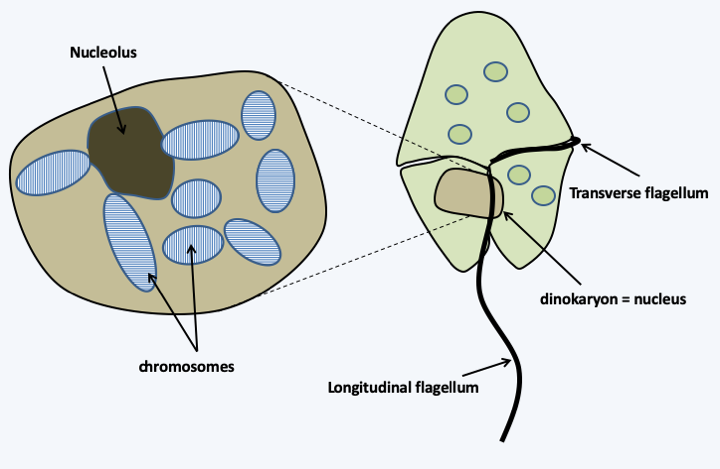

- there are eukaryotes without histones: Dinoflagellata; the structure of their chromosomes is therefore very different from the classical structure (Figure 14) and Box 23).

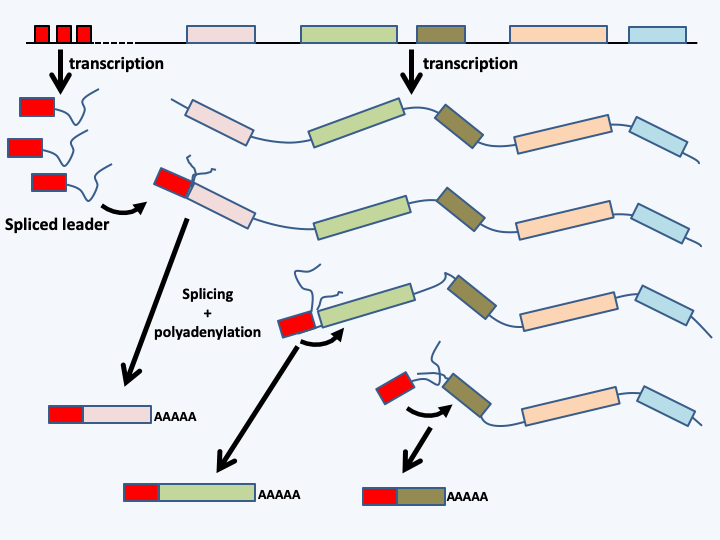

- in Euglenozoa, genes are transcribed as polycistronic mRNA, like bacterial operons (Figure 15). However, these mRNAs are fragmented by trans-splicing and polyadenylation before being exported into the cytoplasm. This mechanism is also present in Dinoflagellata and some animals.

Figure 14.

Dinoflagellates, such as Gymnodinium sp. on the right, are photosynthetic unicellular protists exhibiting several non-canoical peculiarities. Of these, the absence of histones is particularly noteworthy. Correspondingly, the DNA content of the nucleus has greatly increased and can reach 280 billion base pairs in some species! Chromosomes are always condensed, with DNA taking on a liquid crystal organization. Soluble DNA loops are present at the periphery of chromosomes and are the site of transcription. Due to its unusual structure, the nucleus of Dinoflagellata is called the dinokaryon. It divides in a non-canonical way without a classical figure of mitosis. Likewise, sexual reproduction has been demonstrated in some species without detection of classical meiosis.

Figure 15.

Mechanism of fragmentation of polycistronic mRNAs in Euglenozoa. The genes are transcribed in the form of polycistronic mRNA which may contain several dozen coding sequences. A spliced leader is separately transcribed from a locus containing multiple copies of the gene. Each copy has its own promoter. The spliced leader is added by trans-splicing, a reaction that binds the head to the 5 'end of the mRNA by a reaction identical to a conventional splicing (or cis-splicing), except that it involves two distinct mRNA molecules. At the same time, a polyA tail is added. The choice of the polyadenylation site is directed by the position of the splice site located at 3 ’indicating a coupling between the two reactions. Together, the two reactions result in classical monocistronic messengers of eukaryotes.Mitosis and meiosis can exhibit non-canonical characteristics: This is obviously true for eukaryotes without histone, cited above. But this is also the case for certain Oomycota of the genus Saprolegnia and Apicomplexa of the genus Aggregata in which the chromosomes do not cluster on a typical metaphasic equatorial plate. In many other cases (Trypanosomida, Parabasalia…) the involvement of the microtubule network in the separation of chromosomes is not standard. More interestingly, there are eukaryotes with a simple internal structure and which are in particular devoid of mitochondria and therefore function with anaerobic metabolism. This concerns about a thousand species. It was quickly possible to unambiguously match, on morphological and biological criteria, certain species with known groups. They are either Eumycota, or Ciliophora or other protozoa. It is then clear that these organisms have secondarily lost their mitochondria. On the other hand, four groups of organisms have long posed problems because they do not clearly resemble any large known group: the Metamonadina, the Microsporidia, the Parabasalia, and the Archamoebae. Biologists therefore thought that these organisms were intermediaries between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. However, these organisms are all parasites. We can therefore consider two hypotheses. First, they are indeed simple. Second, their ancestors were complex, and after the transition to parasitism, they evolved a simplification of their structure. We know that parasitism promotes a simplification of organisms in the form of reductive evolution.

The first evidence that made it possible to decide between these two hypotheses was the detection in the nuclear genome of genes whose encoded proteins are known to function exclusively in the mitochondria. Indeed, if these organisms derive by simplification from eukaryotes with mitochondria, it is possible to find such sequences. In the four problematic cases, genes whose products function in the mitochondria, including for example the chaperone protein cnp60 which allows the folding of proteins imported into the mitochondria, were found in the genome. However, further evidence had to be provided, as it is possible that these genes were introduced by horizontal transfer more recently, either from bacteria or from other eukaryotes. Additional data was therefore generated: by looking more closely at the intracellular localization. In all cases, structures resembling modified mitochondria could be discovered:

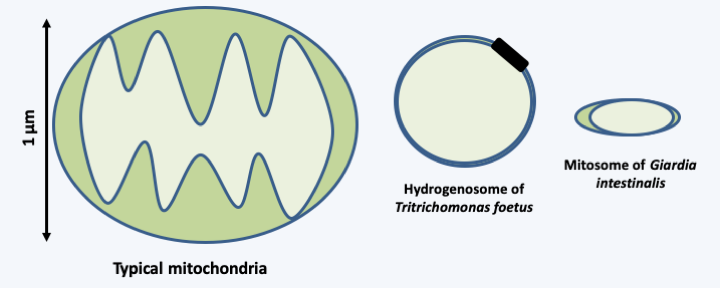

- hydrogenosomes, which ensure the production of ATP without consumption of oxygen but with excretion of H2. They were known for a long time because these organelles are also found in ciliates or anaerobic fungi.

- mitosomes, which in many anaerobic eukaryotes remain the site of iron/sulfur (Fe-S) center assembly, a function also performed by the mitochondria.

These organelles are bordered by two plasma membranes, like the mitochondria (Figure 16). Finally, the genome sequences have made it possible to refine the phylogenetic positions of the problematic groups by establishing molecular phylogenies based on numerous sequences and therefore possessing strong statistical support: Microsporidia are degenerate fungi, Metamonadina and Parabasalia are Metamonada, a group with aerobic representatives, and Archamoebae are Amoebozoa close to slime molds and other breathing amoebae.

Figure 16.

Comparative structures of mitochondria, hydrogenosomes and mitosomes.In conclusion, all eukaryotic groups have in fact had mitochondria in the past. Most likely the parasitic lifestyle of organisms currently without true mitochondria has led to a regression of these organisms, which obscured their origin until recently. All these groups have at least one relic of the original mitochondria. However, the study of unicellular protists is extremely partial. It is therefore not impossible that true primitive eukaryotes will be discovered in the future. At the end of these discoveries, there thus always remains a fundamental difference in complexity and/or functioning between eukaryotes and prokaryotes. A question arises: what is the origin of eukaryotes?

Back to chapter index