Cosmopolitanism and endemism

Back to main indexTo estimate the overall diversity of eukaryotes, estimates must be made from the data obtained for each biotope and the number of potential biotopes. Some studies then extrapolate these data to define global biodiversity. For example, in a given region, the number of Eumycota species is always greater than the number of Embryophyta (land plants). We could therefore conclude that there are more fungi than plants. But, an important point is the endemism (presence only in a precise geographical region) versus the cosmopolitanism (presence in a vast geographical region; in the extreme in the whole world) of the species. Indeed, it is possible that fungi are more cosmopolitan than plants and therefore the number of fungal species is overestimated.

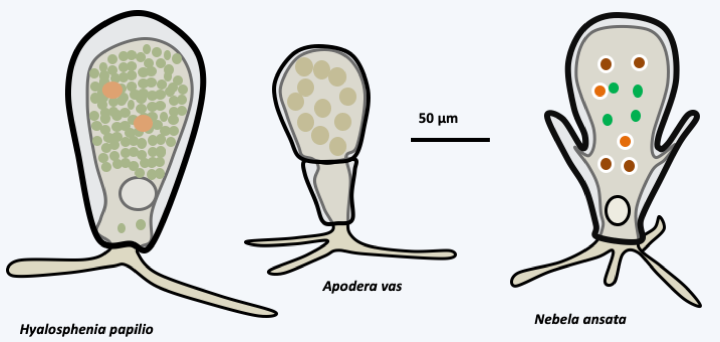

Once again, due to the lack of data, the structure of protist populations is poorly understood. A recent analysis of the structure of the morphospecies Hyalosphenia papilio (Figure 71), an amoeba of the phylum Amoebozoa, using the sequence of the mitochondrial gene encoding the cytochrome oxidase (COI) subunit I, shows that there are in fact probably a dozen genetically independent lineages, whose percentages of similarity at the level of the COI gene vary from 1% to 11.6%. The different lineages seem specific to different continents but the majority of genetic differences can be explained by effects of the nature of the environment; these amoeba live in bogs. Likewise, it seems that amoebae of the species Apodera vas (Amoebozoa,Figure 71) are not found in the northern hemisphere, although this is the most studied region, suggesting that these amoebae are not cosmopolitan, but subservient to regions from Gondwana (Africa, South America, Australia and Antarctica). Finally, a last Amoebozoan amoeba, Nebela ansata (Figure 71), appears to be restricted to peatlands in the northeastern United States. The same type of structuring is found in fungi. For example, Craterellus tubaeformis (Figure 72) is a morphospecies, which seems to contain at least three genetically independent lineages, one in North America, one in Europe, and the last seems to co-exist in Quebec and in Europe. Modeling and measurements show that 95% of the basidiospores emitted by a Basidiomycota carpophore drop after less than one traveled meter, suggesting that many fungi do not disperse easily over great distances. In fact, as for Craterellus tubaeformis, a detailed analysis of the populations indicates that very often there is a structuring according to the geography in subspecies or even in species. For example, for many fungal parasites, speciation would be related to the host, as in Ophiocordyceps, parasites of ants of the genus Camponotus. While it was thought that only Ophiocordyceps unilateralis was involved, the results of the analysis of a small region, the “Zona da Mata” of the Brazilian forest, revealed four new species, each specific to the Camponotus species they parasitized. Extrapolation on a global scale indicates that several dozen, if not hundreds, of species parasitize Camponotus, each present in the range of their host! In contrast to previous results, analysis of ribosomal genes from flagellates from hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean showed that the same species are most often found as in the fjords of Denmark. Similar analyzes indicate that the same planktonic Foraminifera are present in the Arctic and Antarctic Oceans.

Figure 71.

Three Amoebozoa amoebae with different geographic distributions. These three amoeba inhabit peatlands. Hyalosphneia papilio is a morphospecies with at least twelve genetically independent lineages found around the North Polar Circle; Apodera vas inhabits only the regions deriving from Gondwana (southern hemisphere) and Nebela ansata only in the northeastern United States.In summary, it seems that like animals and plants, protists, including fungi, often have complex structures of species with more or less isolated lineages at the genetic level; each of the lineages showing more or less extensive adaptations to particular biotopes. However, it is probable that the ranges of the different lines are wider than in the case of animals and plants. This is not surprising, in fact resistant structures such as spores or cysts can be transported by wind or sea currents over great distances and examples where the same species are found around the world are frequent. In contrast, some protists clearly have very restricted ranges. As a result, some researchers believe that cosmopolitanism is a general case and that almost all microorganisms are already known. For others, endemism is grossly underestimated. It is probable that the truth lies between the two positions and that, depending on the groups of protists, endemism or cosmopolitanism are preponderant.

Figure 72.

Craterellus tubaeformis. This mushroom presents several varieties well known to gastronomic mycologists. The variety represented here is the variety 'lutescens'. Sequencing of the ITS barcode region of the different varieties suggests speciation related to geographic distribution with three independent lines. North American individuals (type 1) are generally genetically different from European individuals (type 3) with 17% divergence in the ITS region. One of the three types (type 3) is however found in Quebec and Belgium.Back to chapter index