An overview of the diversity of eukaryotes

Back to main indexAlthough the inventory of eukaryotes is not yet complete, the data already available and confirmed by molecular phylogenies provide an overview of their evolution. Nevertheless, this view will probably change in its details as new groups are described. Indeed, if the discoveries of new species of animals and plants are still frequent, those of larger groups (genera, families, orders or classes) are now exceptional in these two groups. On the contrary, descriptions of such taxonomic ranks, or even new phyla, in the case of protists are not at all uncommon. For example, in 2011 the Rozellida, also known as Cryptomycota, were described. These fungal-related organisms were previously known only by the genus Rozella and classified among the Eumycota. Metagenomic analyzes have shown that these organisms are ubiquitous in aquatic ecosystems and very genetically diverse. The Rozellida now form a new phylum.

Likewise, the number of species within each group is often open to discussion. For example, Ciliophora are a unicellular group that has characteristics unique to eukaryotes, including the presence of a somatic nucleus and a germline nucleus. Molecular phylogenies have confirmed the monophyly of the group. However, the figures found in the scientific literature for the number of species fluctuate between 4,000 and 40,000! A first estimate combined a bibliographic approach of the species described with direct sampling. This first method estimates the total number of morphospecies at 3,750. 800 are found in marine sediments and 1,370 in freshwater sediments. Direct observations of sediment samples estimate the number of marine species at 600 and of freshwater species at 730. The two estimates therefore converge to establish a limited number of Ciliophora morphospecies. Analysis of the distribution of these species shows that they are most often cosmopolitan. In summary, the Ciliophora would show a relatively low morphological diversity with a cosmopolitan distribution and most of the species would already be described. In contrast, a statistical analysis suggests that only half of the morphospecies have been described because not all habitats have been analyzed in detail. The actual number of species would then be close to 40,000 because genetic diversity data suggests that each morphospecies corresponds to about ten species. In this second estimate, 90% of the species remain to be described. This type of controversy is not unique. Indeed, even more extreme figures are sometimes proposed for Eumycota. About 80,000 species are currently described. It is generally estimated that more than one million species remain to be described. This figure comes from estimates based on the number of biotopes that remain to be analyzed and the fact that the Eumycota seem less cosmopolitan than often assumed. Indeed, many species that have a restricted habitat are known, because they live for example in exclusive association with plants or insects. Often their host spectrum is restricted to a genus or even a species or a variety. In areas where flora and mycoflora are well known, such as Western Europe, there are six times more species of fungi than plants. This allows to estimate the total number of species of fungi to 1.5 million, because there are approximately 250,000 species of plants in the world. This figure does not take into account insect pests/mutualists. Some mycologists argue that there may be at least as many, if not more, species of fungi as there are insects. As there are currently several million species of insects, that would put the number of Eumycota fungal species at 10,000,000! If this estimate is correct, at the current rate, it will take 10,000 years to describe all these fungi… Despite our partial knowledge of the biodiversity of protists and the difficulties in estimating the number of their species, contemporary data clearly shows that depending on the eukaryotic groups, the diversity of species appears to be highly variable. Some groups are only known by a few species, while others include several thousand or more species. Overall, the takeaways from eukaryotic biodiversity as it is known today:

- There are four lineages that have had great evolutionary success, because they include very many species, several hundreds of thousands at least, and have invaded almost all biotopes: animals or Metazoa, green plants or Embryophyta, Eumycota and Stramenopila and more specifically the Ochrophyta “algae”. These organisms have often evolved all possible types of life styles: free life, parasitic, mutualist, aquatic or aerial life, etc.

- the existence of a small number, currently around ten, of groups with intermediate success. The number of species is in the thousands, a few dozen at most, with a habitat that is often more restricted but whose biology is very varied. Examples are Ciliophora or Haptophyta.

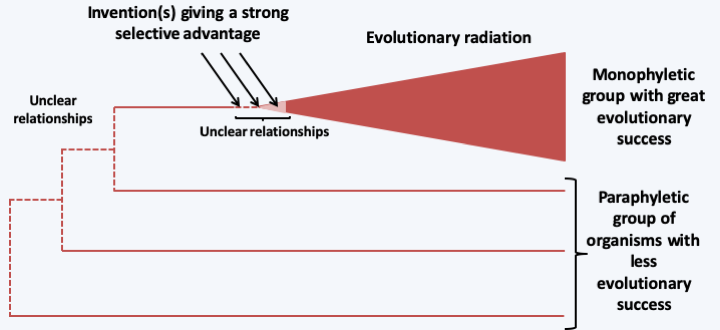

- the existence of a swarm of other lineages with few species and often possessing specific biologies. For example, Fornicata or Percolozoa, also called Heterolobosea, are only known by a few dozen species. Yet these organisms have a biology that is very different from the majority of other eukaryotes. While a few of these lineages are clearly independent of the major eukaryotic lineages, most are in fact related to organism groups with high evolutionary success (Figure 80). As in the case of evolutionary radiations for which the phylogenetic signal is too weak to order the different lineages that result from it, their placement is most often difficult due to the age of the divergences of the small number of available species.

Figure 80.

Typical result of a phylogenetic analysis in eukaryotes.In addition to these well-defined groups, there are still organisms known only by DNA sequences from metagenomic studies. Conversely, many species, especially flagellates and fungi, have been morphologically described but no sequence is available. Often these species are rare and not available in collections. While most of the fungi will join one of the Eumycota branches already described, the flagellates could define new lineages independent of those already described.

Back to chapter index