The phylogenetic classification of eukaryotes

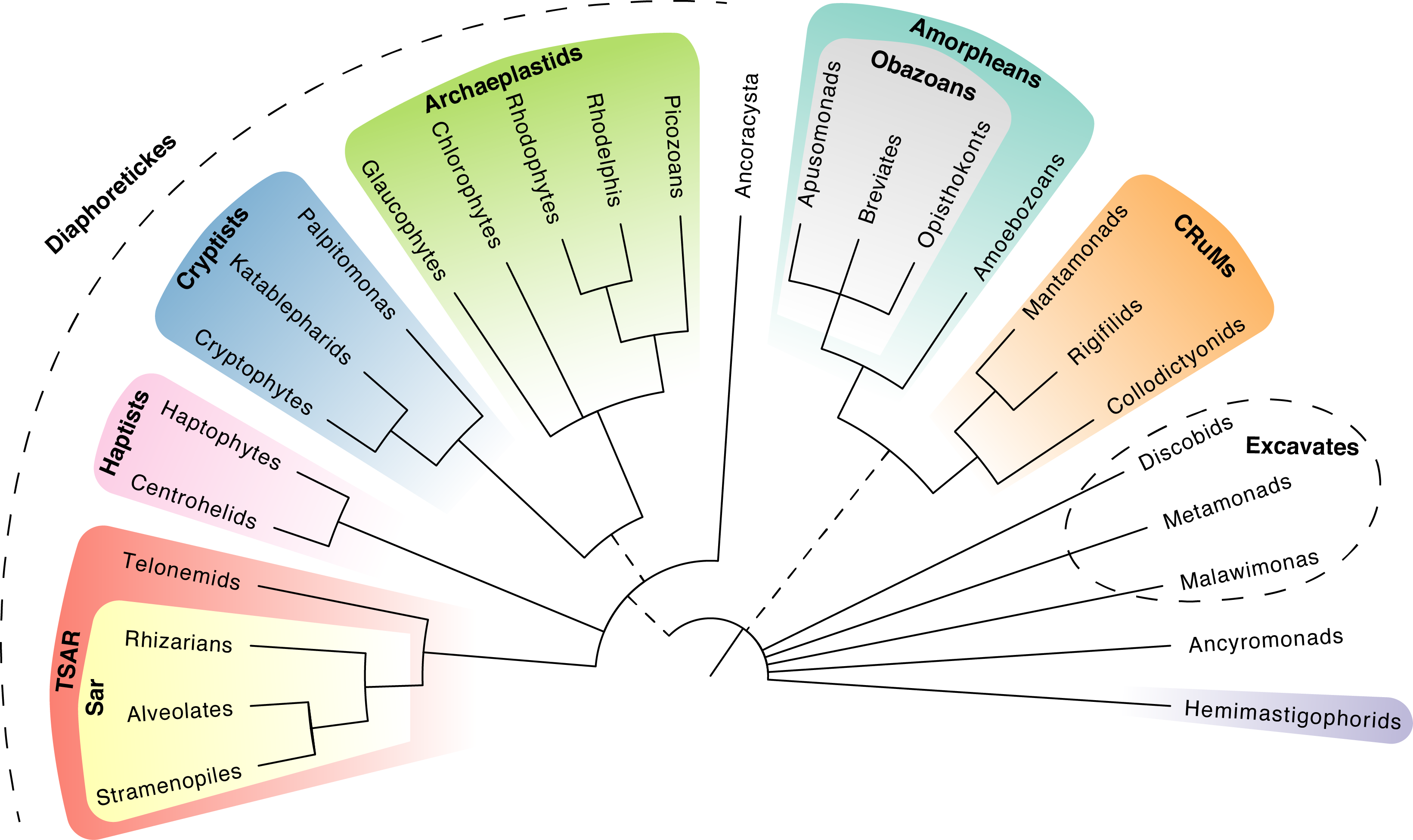

Back to main indexMolecular phylogenies (Figure 81) currently suggest grouping most eukaryotes into several monophyletic lineages of which the most species-rich groups are: Opisthokonta, Amoebozoa, Archaeplastida, Stramenopila, Alveolata, Rhizaria, Haptista, Cryptista, and a last group whose status is in constant modification: the “Excavata”. These monophyletic groups are well established and will probably not change more. However, it is very likely that Excavata disappears, because most of the species of this group have not been molecularly analyzed. Data already obtained suggest that this line is polyphyletic.

Figure 81.

The eukaryotic Tree of Life. This consensus tree is based on several recent phylogenomic studies. Coloured groups represent 'supergroups', which are broad, monophyletic groupings of eukaryotes. Unresolved relationships are depicted as multifurcations, while dashed lines represent uncertainties in the monophyly of groups. Figure adapted from Burki et al. (2019). Trends in Ecology and Evolution.These eukaryotic major lineages seem to form even larger assemblages (though several protist groups have not been confidently assigned to any larger assemblage, for example the Anyromonads,Figure 81): the Amorphea, the Diaphoretickes and the problematic “Excavata”. These three large clades contain species with highly diverse forms and functions making it is impossible to find synapomorphies for them. The term Amorphea (= without form) also reflects this fact. It can be noted, however, that the endosymbiosis, primary, secondary, etc. of the plastids are produced exclusively by the Diaphoretickes. Each of the five lines of this supergroup contains algae, but not exclusively.

Currently, the order of branching of these three large assemblages is very uncertain. A molecular signature, the fusion of genes encoding the synthesis of thymidylate and the reduction of dihydrofolate, has been proposed to encapsulate the tree between the Amorphea (or Unikonta), in which the genes are separated, and the other eukaryotes (or Bikonta), at which they are merged. This rooting allowed to separate the eukaryotes into two sets based on their mode of propulsion. However, this signature is now less clear because the two genes are fused in Thecamonas trahens, a flagellate clearly placed in Amorphea by molecular phylogenies, probably as an old group of Opisthokonta. In fact, the term Unikonta has been abandoned because many species of Amoebozoa have two flagella. Moreover, it seems that the merged form of the two genes, rather than two separate genes, would be the ancestral state. The tree would then be rooted in the Excavata and placing the other eukaryotes into two distinct lines. In fact, one phylogenomic study grouped a part of them, the Malawimonadea and the Diphyllatea, together with the Amorphea (or Unikonta) in a line called “Opimoda” and another ensemble merged the Discoba and the Diaphoretickes under the name of “Diphoda”. This rooting is perfectly compatible with the theory of phagotrophic origin of eukaryotes. The ancestral eukaryote would then, regarding morphology, be that of a small flagellate possessing two flagella and a ventral furrow by which it phagocytoses its prey. Its cellular body would also be able to deform to allow amoeboid movement. However, the position of the root of the eukaryotic tree is still very contentious.